Everlasting Traditions in Herbal Medicine

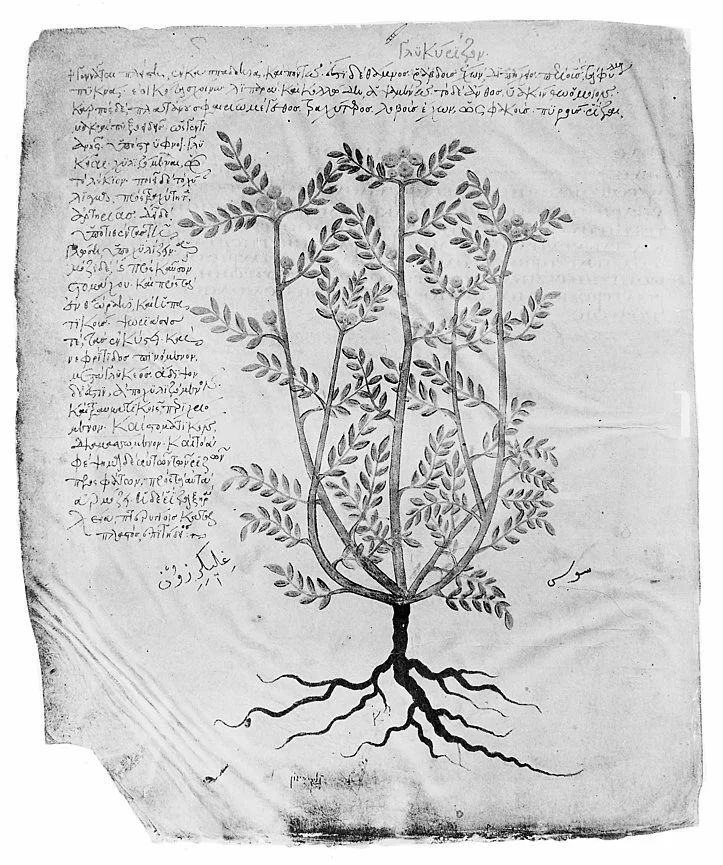

The licorice plant as depicted in De Materia Medica by Dioscorides in the Julianae Aniciae Codex copy currently in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

This article was initially published in The National Herald on August 17, 2019.

The practice of herbal medicine in antiquity was not separate from everyday living; it was an integral part of every custom, celebration, and recipe throughout the ancient world. In ancient Greek mythology, there are countless associations between ancient gods and medicinal plants, many of which have names related to their Greek origin. Sacred ceremonies involved the use of both culinary and medicinal herbs for secret recipes while ancient scholars wrote extensively on their uses for both serious and acute illnesses. Ancient kings sought to extend their empires not only to have unlimited access to gold and other highly coveted minerals, but also to the valuable treasures of the plant world – herbs, spices, perfumes, and incense – to ensure the health of their civilization, and thus, a long-lasting legacy.

The ancient Greeks are most notably known for their contributions to modern medicine through the teachings of Hippocrates (460-370 BCE) known as the father of modern medicine and whose Hippocratic Oath continues to bind modern-day physicians to “first do no harm.” To explain how the body became sick, he applied the theory of the four bodily humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. When these were balanced, good health was enjoyed; whereas disease and illness resulted from an imbalance of one or more of these bodily substances. His infamous quote, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,” truly reflected the integral role of plants and their healing powers in maintaining a thriving ancient civilization.

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE), who wrote extensively on the diversity of plants and animals, expanded the theory of the four humors to correspond to the four elements of fire, air, water, and earth. Each of these elements have qualities of hot or cold and wet or dry, and corresponded accordingly: fire is hot and dry, air is hot and wet, water is cold and wet, and earth is cold and dry. These qualities were then related to the four humors of the body: blood as air, phlegm as water, yellow bile as fire, and black bile as earth. Ancient physicians sought to identify the imbalances in the body according to the qualities exhibited by the patient, and herbal medicine was administered to help restore the body to its natural balanced state. Take, for example, the qualities of oregano (hot and dry) and imagine how critical it could be to heal someone suffering from a cold and congested state. (If you’ve ever taken oil of oregano to stave off a cold, you’ll more easily understand this concept.)

Another theory employed during ancient times and which could possibly explain the origins of how people first understood the medicinal properties of plants was the Doctrine of Signatures. This theory, which continues to be referenced in present day, states that plants resembling parts of the human body or resembling their action on the body hold curative properties for that body part. Examine the shape of a walnut and notice its similarity to the shape of the human brain. Or look at the bright yellow flowers of St. John’s Wort and imagine how it brings light to the soul, dispelling depression and anxiety. Ancient civilizations did not separate the divine world from the natural world, and therefore, the design of medicinal plants was the result of mystical and sacred intentions. Intertwining theology and natural sciences, a practice that would continue well into the Middle Ages, was a central aspect of medical thought and an important component for healing.

While these ancient theories are no longer used in modern medicine, they continue to remain a critical resource to understanding how people once understood the natural world and how they sought to learn about the human body without the modern techniques we now have. Two notable ancient Greek writers, Theophrastus of Lesvos (372-286 BCE) and Dioscorides of Asia Minor (40-90 AD), propelled the study of natural history and herbal medicine through the wide distribution of their surviving texts, Enquiry into Plants and De Materia Medica, respectively. As a student of both Plato and Aristotle, Theophrastus was heavily influenced by his teachers and wrote his nine-volume book, Enquiry into Plants, to provide detailed descriptions of the natural environment, including the classification and identification of varieties of trees, shrubs, and plants. Today he is considered the father of botany.

Dioscorides, the ancient scholar most celebrated for his contribution to the study of herbal medicine, was a medical botanist and Greek physician in the Roman army who achieved world-renown fame with the publication of De Materia Medica. His five-volume series, Latin for “On Medical Material” or in ancient Greek as Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, describes approximately 600 plants for more than 1,000 traditional medicines and would become the basis of European and Western pharmacopeia for centuries after. It was subsequently translated into Latin, Arabic, Italian, German, Spanish, French, and finally into English in the 1600s. For the first time in known history, herbal medicine was documented and distributed across the ancient world and the publication would be extensively referenced for the following 1,500 years.

These records provide an exciting and comprehensive resource not only for herbalists interested in the traditional and folk use of plants, but also for botanists, environmentalists, archaeologists, and historians, as well as for those whose Greek ancestors wove these practices into their family customs.